Exhibitions: Photos by Weems

Photos by Weems Curated by Maxine Payne March 23-April 29, 2023

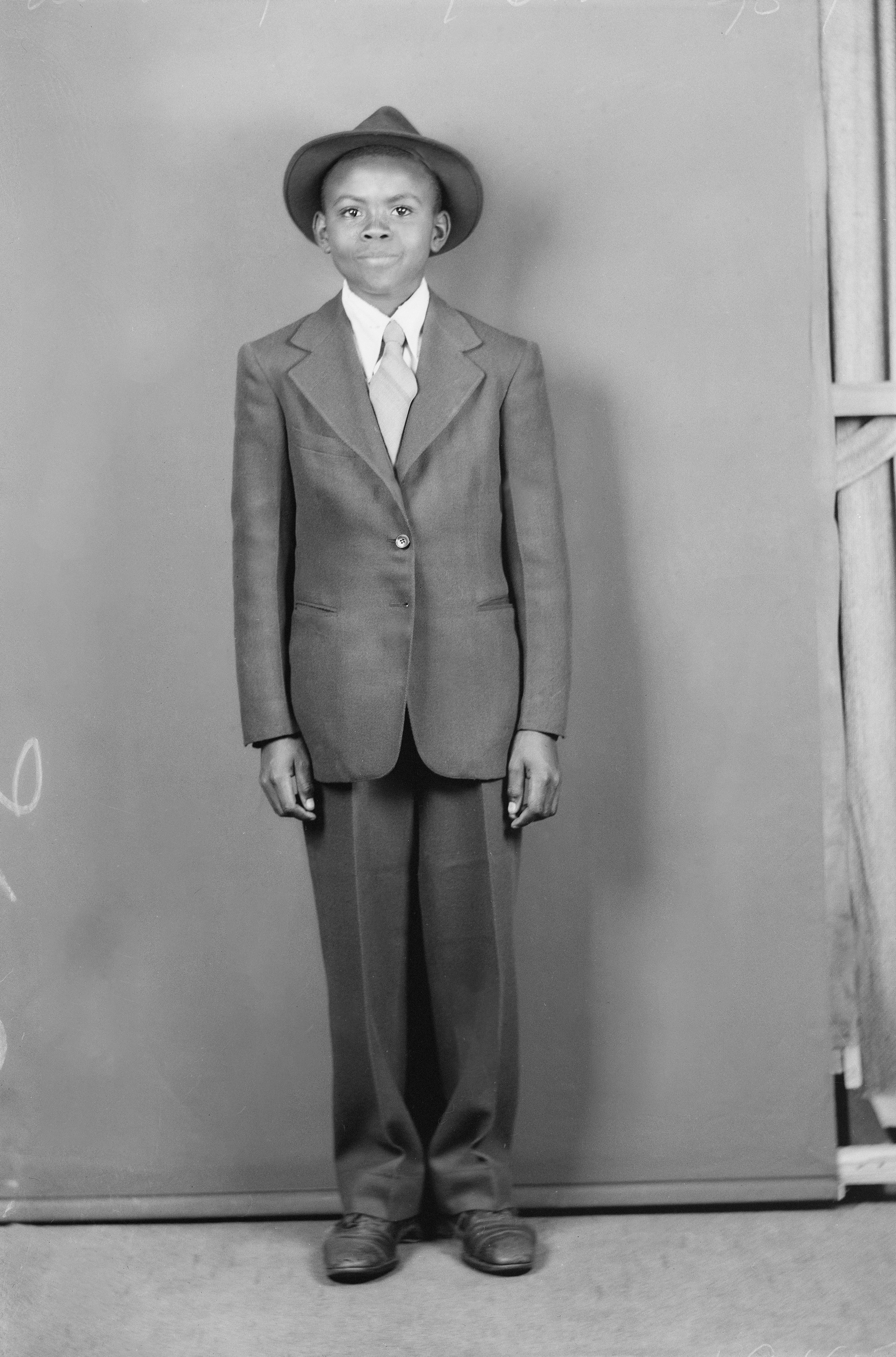

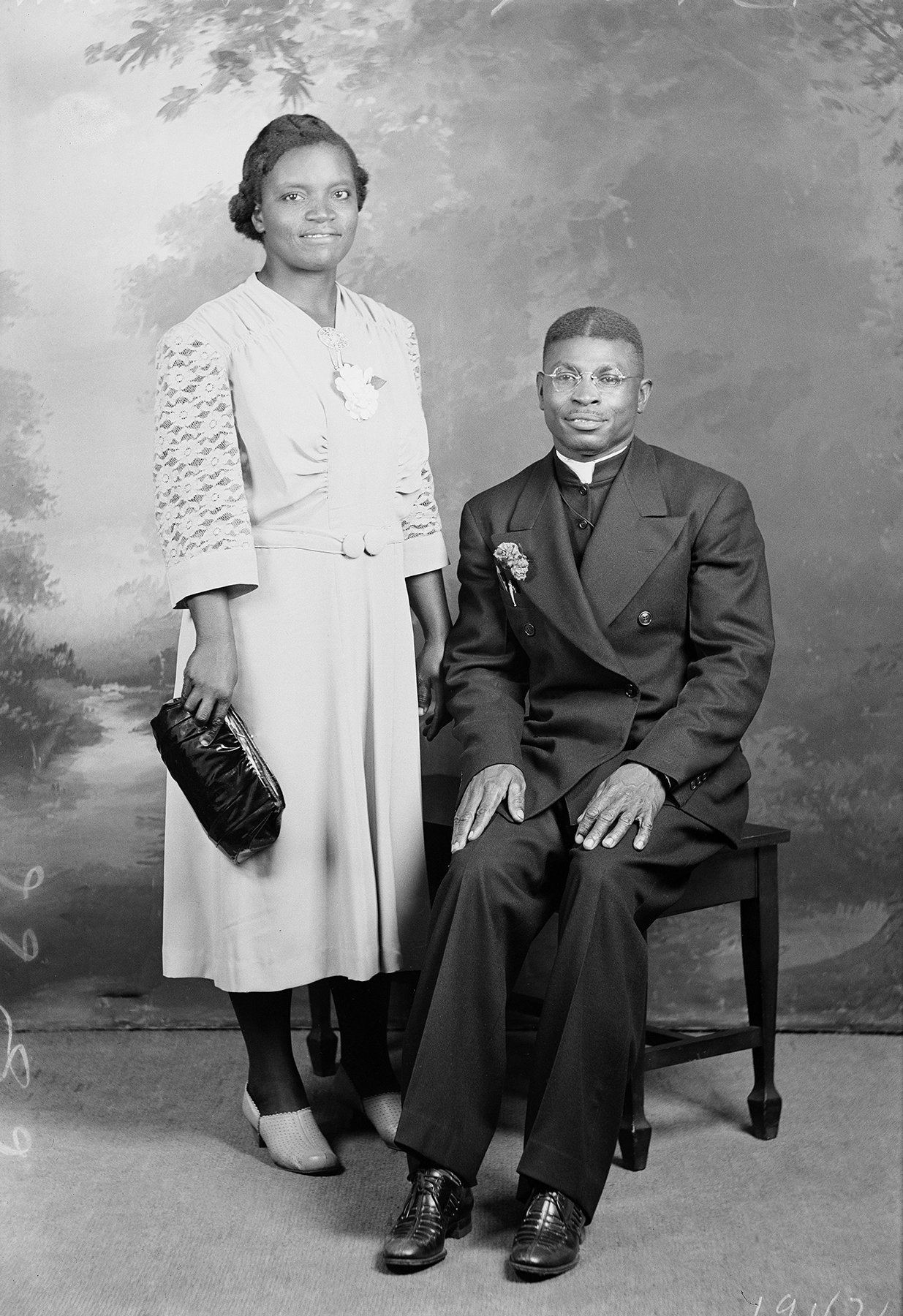

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Photos by Weems Curated by Maxine Payne March 30 – May 20, 2023

“Do all the good you can. In all the ways you can, in all the places you can, for all the people you can, while you can.”

-Clara White

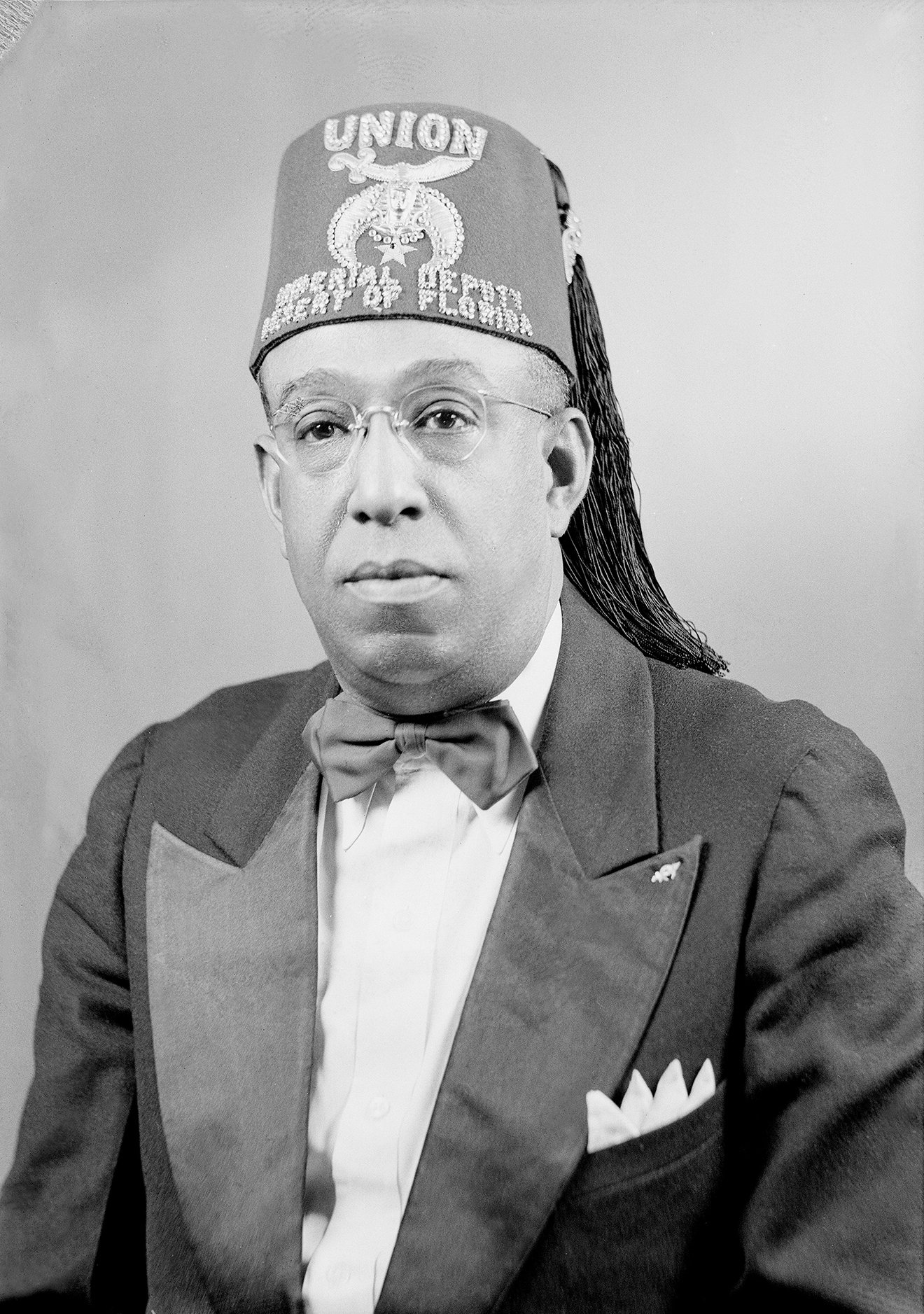

It’s 1929 in Jacksonville, Florida and at the corner of West Duval and Broad Street sits a small photography studio. Inside the door, one finds simple backdrops, a roll of neutral tone paper, and drapes forming vertical lines that––against a linoleum floor––define the space for someone to stand. These velvety conduits offer the perfect tonal range desired by black and white film photographers; the carefully chosen (but mass produced) studio backdrop of a fictitious, bucolic landscape transports the subject and viewer into a state of timelessness. Props are at the ready: a small chair for a child, a variety of pedestals to seat a husband or sibling, a versatile piano bench that is just the right size for a young woman to show off the fullness of her elegant skirts. A handmade sign reading Photos By Weems identifies this place as the studio of Ellie Lee Weems, a chronicler and archivist of African American life and culture in a bygone era.

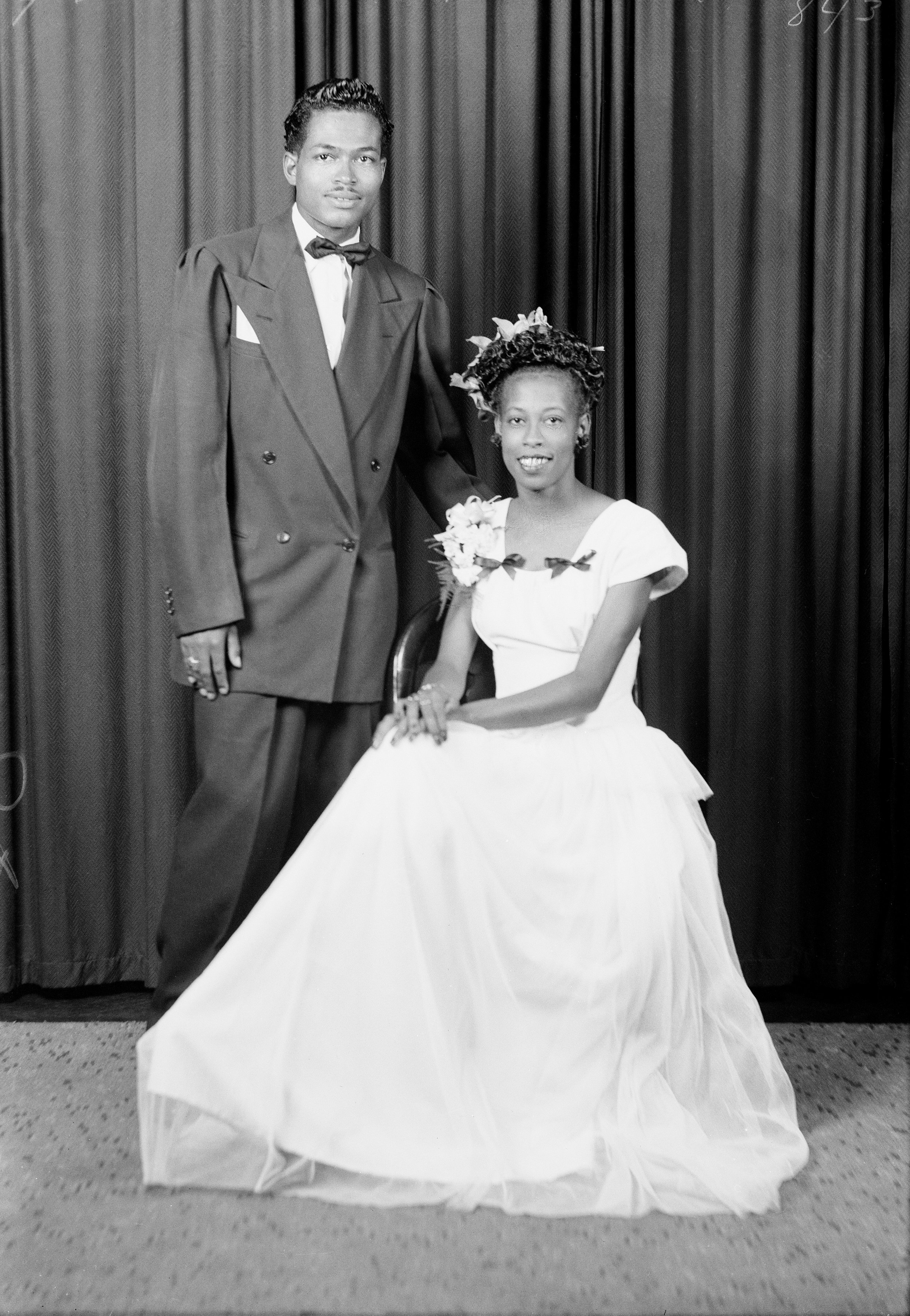

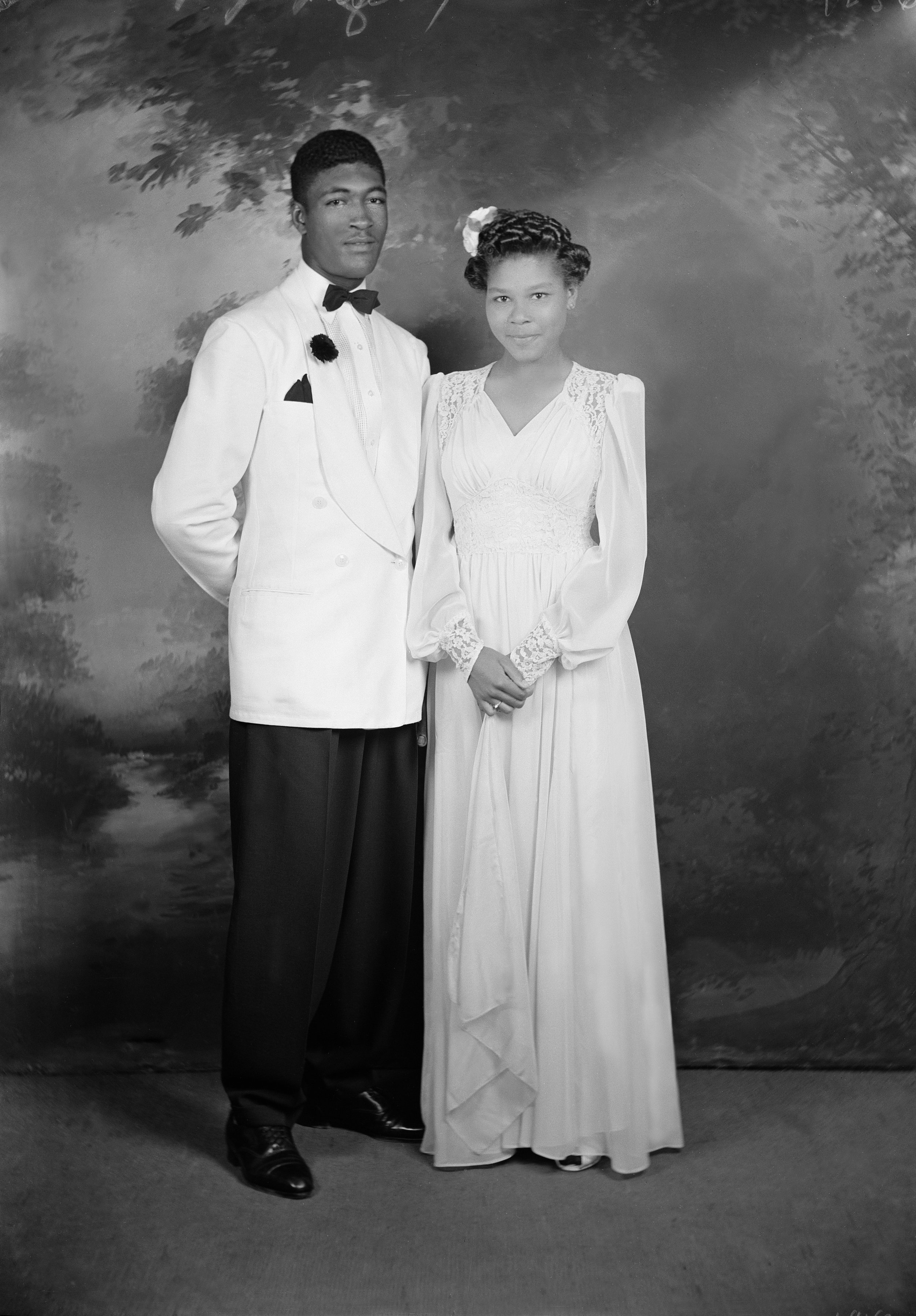

Photos By Weems presents thirty-four portraits, edited from thousands more, made by Black Jacksonville’s preeminent studio photographer. Separated by time, space, social, and political climate, we do not know the people in these images, but they feel familiar. Young girls wear cotton dresses with Peter Pan collars, puffy sleeves, and full skirts. Older women wear gloves, corsages, earrings, necklaces, hats, broaches, stockings, and sensible but elegant high-heeled shoes, often with broguing. Some of the women are in practical day clothes, others are in appropriate church going dresses or formal wear. The men sport double-breasted blazers; some of the young men wear the precursor to what would become known as a “Zoot suit.” Others don wide neckties, two-tone Oxford shoes, boutonnières, or fedoras. Pens, silk squares, and pocket handkerchiefs are tucked into breast pockets. Men are directed to look straight at the lens, women and girls sometimes off to the side. It is obvious that Mr. Weems’ subjects trusted him; they respected his expertise, as evidenced by the photographs he made.

Our relationship with photography is vastly different in the digital and social media era than those who lived in an analog world. We must therefore consider Weems’ work in the context of time and place to better understand the people represented. When, where, and by whom images are made are vital to our understanding: what does the studio portrait tell us about the subject, and what does our interpretation of the studio portrait reveal about ourselves? In looking at these photographs, it’s clear that Weems wanted to represent his subjects in the best way possible. Through the compositions, lighting, and direction of a masterful photographer, beautiful and successful people were recorded in images that they could be proud of. Here are angels, queens, scouts, and soldiers.

–Maxine Payne

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Ellie Lee Weems, Untitled, 1930-40s.

Words by Saundra Murray Nettles

Like many photographers of his time, my great-uncle Ellie Lee Weems conducted business on the first floor of his Jacksonville home base on Beaver Street.* Trusting my siblings and me to observe the “look, don’t touch” rules, Uncle Ellie allowed us to spend time on the front porch or in his studio where we would peek into the darkroom when the door was open, use the mirror in the powder room where customers could make last minute fixes to their hair, or walk around the big room examining cameras and lights on stands. On the second floor, he and his wife Mae, a public health nurse, had established a comfortable and elegant apartment decorated with fine and vernacular furniture. When clients entered the house to sit for a photo, we children would go upstairs to the private space.

Uncle Ellie’s sister, my grandmother Beulah Weems Rice, lived in Atlanta. Beulah was the keeper of the family’s visual archives. Although there were images made by other relatives, she cherished the ones her brother produced and proudly pointed them out to visitors. On the walls of her den, she had hung hand-tinted photographs of Ellie and Beulah’s parents as well as images of paternal ancestors, enslaved as children on the Weems plantation in Henry County Georgia. In albums, there were studio shots of each of the five children she had with my grandfather Rice, in addition to images of their 14 grandchildren. On their way to engage in advanced studies (Mae at the Medical College of Virginia St. Philip School of Nursing and Ellie at the Winona School of Photography in Indiana), the couple would spend time in Beulah’s den chatting about the photos while Ellie smoked his favorite cigar and grandchildren stopped by for hugs and kisses.

Looking back, I can see the familial roots of a visual practice that captured the often brief, but passionate exchange between photographer and sitter. Clients spoke about how they especially valued Weems’s portraits of individuals and families for their intimacy and dignity. Mutual respect and affability shone through the images that bore his signature, “Photos by Weems.”

–Saundra Murray Nettles

Ellie Lee Weems

Ellie Lee Weems (1901-1983) was born in McDonough, GA and attended Tuskegee Institute. There he studied under C. M. Battey, founder of the school’s Photography Department. After Tuskegee, Weems moved to Atlanta where he practiced photography; in 1925 he met and wed Willie Mae Morris in Chattanooga. By 1928 he had worked as the proprietor of the Paul Poole Photography Studio in Atlanta. In 1929, Weems moved to Jacksonville where he was a successful photographer for half a century in 3 different studios. In addition, Weems was renowned in Florida for his images of community life and the physical fabric of cities and towns. He closed his last studio on Beaver Street in the early 1980’s when his nephew took the Weems to Georgia.

Maxine Payne

Maxine Payne is a photographer living and working in Arkansas, where her grandparents raised her. She received her M.F.A from the University of Iowa where she was also an Iowa Arts Fellow. Maxine was selected a Fellow of the American Photography Institute at New York University, as well as a Fellow of the College Art Association. Currently a Professor in the Art Department at Hendrix College, she works to find ways to engage community in her work and speaks to the idea of place. Maxine was awarded the 2013 National Museum of Women in the Arts, Arkansas Fellowship for her photographic work. Her collaborations with Phillip March Jones, Institute 193, led to the 2015 Dust-to-Digital publication of “Making Pictures: Three for a Dime.” Currently, Maxine shares the Margaret Berry Hutton Odyssey Professorship with author Tyrone Jaeger. Their collaborative project with Hendrix College students and alum, called Audio Visual Arkansas, focuses on collecting digital stories about Arkansans and can be seen at AVARK.net. Maxine collaborated with anthropologist Anne Goldberg documenting the lives of rural women in Costa Rica, the U.S./Mexico border, Africa, and Vietnam. In 2017, Maxine worked with biologist Matthew Moran to document the environment and people of the “Big Woods” region of Arkansas. She has photographed hundreds of Arkansas historic bridges for the Arkansas Highway and Transportation Department since 2004. Maxine has continued her curatorial work with Phillip March Jones on two historic photographic archives, the Massengill family photographs and the photographs of Ellie Lee Weems, both of which are included in The High Museum of Art’s 2023 exhibition and publication Photography and the American South since 1850. Her work can be seen at www.MaxinePayne.com.

Saundra R. Murray Nettles

Saundra R. Murray Nettles is a writer and scholar of environmental and educational psychology. She is the author of Crazy Visitation, a memoir of life with and without a brain tumor, and Necessary Spaces: Exploring the Richness of African American Childhood. She has published academic articles and book chapters on the experiences of marginalized children, youth, and women in formal and informal learning environments.

A Fellow of the American Psychological Association (APA), she is a former president of the APA Society for Environmental, Population, and Conservation Psychology and co-founder and past president of Section 1 (Psychology of Black Women) of the APA Society for the Psychology of Women. Murray Nettles is a 2020 recipient of the Elizabeth Hurlock Beckman award for “excellence in education and inspirational leadership” and a Women’s Studies Fellow of the Institute for Citizens & Scholars.

She is an alumna of Howard University and the University of Illinois School of Information Sciences. Dr. Murray Nettles conducted educational research at the American Institutes for Research and the Johns Hopkins University Center for Social Organization of Schools and taught at several institutions, including the University of Maryland and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

As a retired professor and published poet, she is pursuing her longstanding interests in history of architecture and vernacular photography.

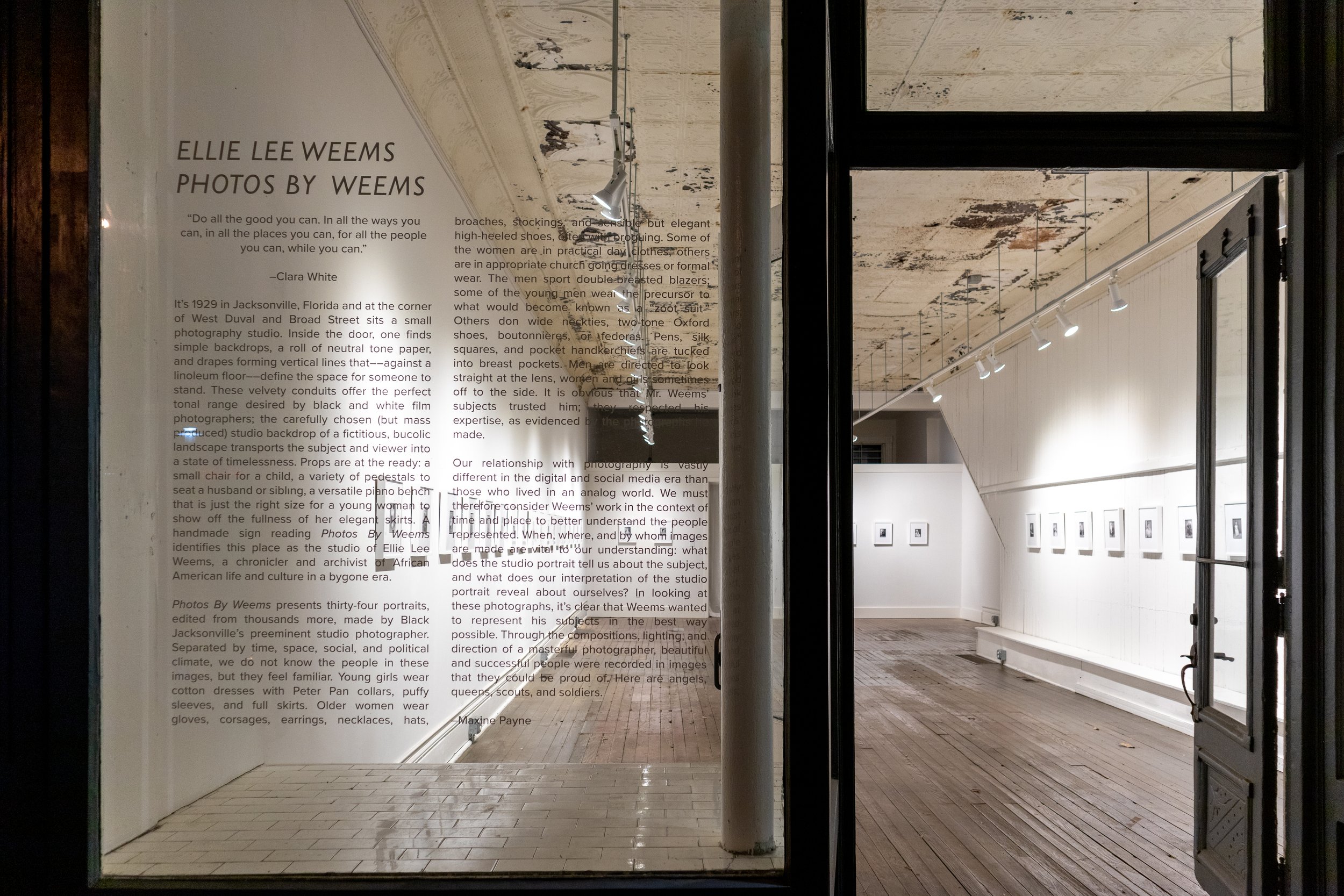

Installation view, photo by Josh Porter

Installation view, photo by Josh Porter

Installation view, photo by Josh Porter

Installation view, photo by Josh Porter

Installation view, photo by Josh Porter

Installation view, photo by Josh Porter

Installation view, photo by Josh Porter